Since 1948, Israel and Palestine have been embroiled in what is famously known today as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yet to have a better foothold for genuine comprehension of the situation, it is crucial to note that the so-called conflict was kicked off by a disparity between Palestinian Jews and Arabs when that portion of the world was declared an Israeli State, on May 14, 1948. In other words, the root of the unending tug-of-war stretches back to events/history of the biblical times.

Ever since, this fateful entanglement – having succeeded in conjoining myth and present-day reality into a perpetually fraught seam – has taken different turns and detours marked by some of the most bestial violence in modern history.

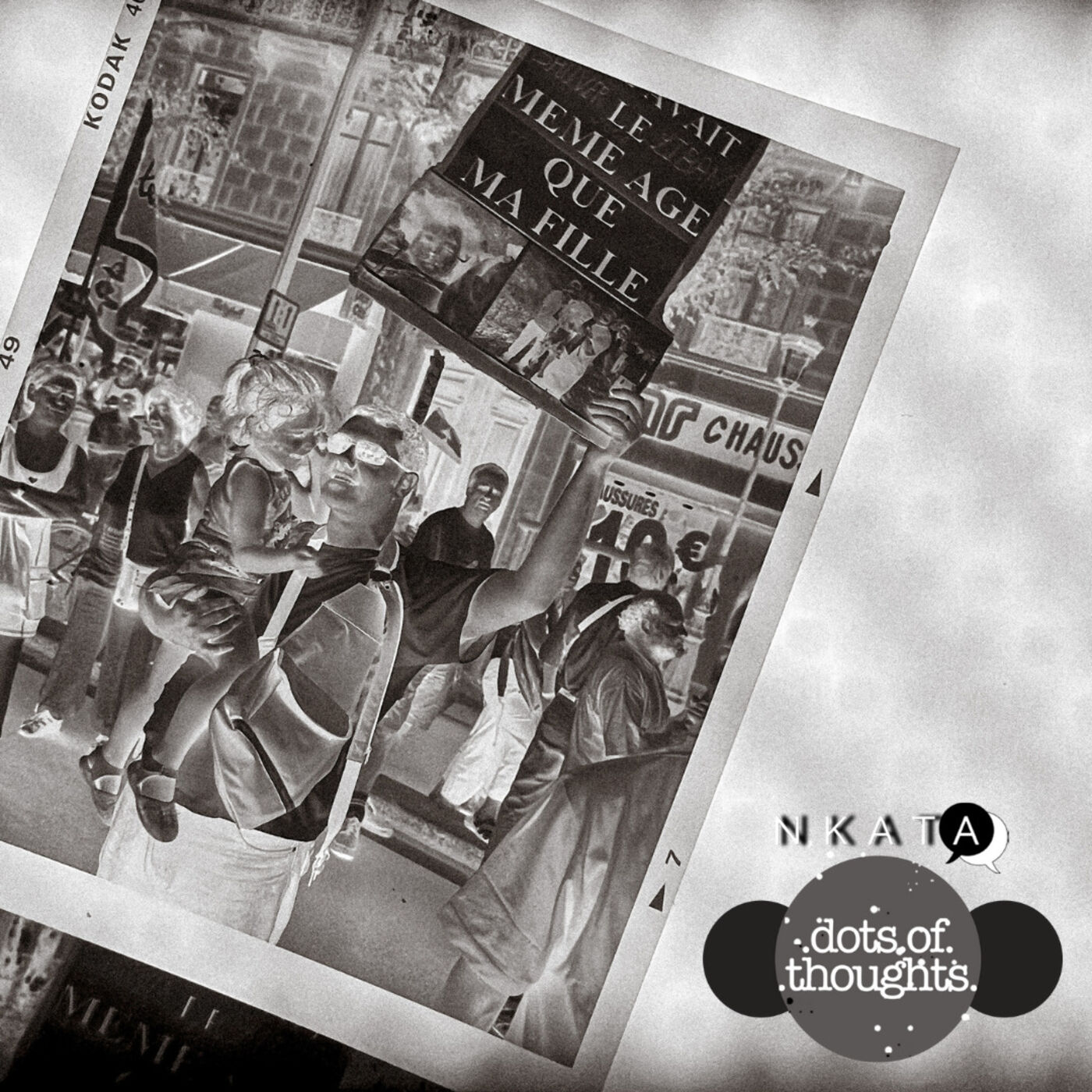

In 2006, I remember photographing, in Paris, the protest against killings that then took place in Isreal and Palestine. In the photo, a father is clutching his little daughter on one hand, while with the other hand, waves a placard that reads “Le meme age que ma fille” (same age as my daughter). I remember feeling deeply struck by this double emphasis aimed at reiterating what should be so obvious: the trail and ensuing threads of human violence – like mitochondria – run and connect to us all.

In this podcast conversation, I caught up with a longtime friend and fellow artist Bahaa Abudaya to discuss the most recent eruption of violence which took place in May 2021.

Bahaa Abudaya’s father was born in 1946 in Ashkelon, a coastal city in Southern Isreal. It won’t be long before his family was displaced and moved to a refugee camp. In the conversation, we dwell on the reality of being in exile in one’s homeland.

Bahaa left Gaza when he was two years old. Since then, he has roamed the earth. Yet he claims: no matter where I go, I always consider myself a Palestinian even though I do not know, from lived experience, what Palestine is as a place. He goes on to explain that this deeply inward, yet unforced identification with Palestine is constitutive of his disposition as one who is in a state of permanent temporality.

“I am never clear where I should be. I have developed a kind of personality through this kind of exile”.

Here, we are presented with the paradox often a fixture of border-bodies: on one hand, a solace accompanies the feeling of never being beholden to a place. On the other hand, there is something about transience that denies one a sense of continuity. Rightfully so, Bahaa concludes that his life is floating somewhere in between these unresolvable polarities.

His Palestine is one he anchors to a memory of displacement. He recalls an anecdotal event that took place when he was ten years old. His grandmother took him to the site where her home once stood before the occupation. The most indelible moment of the visit was witnessing his grandmother shed tears profusely. As a child, he could not understand why absence meant so much for her. Her tears became symbolic of an incomprehensible, ungraspable loss that he would carry with him as a placeholder for what it means to be Palestinian. “Every Palestinian makes his or her own Palestine for themselves”, he said in the podcast. They make their Palestine out of ruins and loss. That is why the picture of young Palestinian kids throwing pebbles at Israeli armoured tanks should be read beyond its photogenic attributes.

The Israeli army, complete with its intelligence apparatus, is one of the most powerful in the world. For that reason alone, this conflict, on the part of the Palestinians, will always be one of bringing a fist to a gunfight. But that fist is clenched tight – always ready to provoke violence as intrinsic to its resistance.

As Bahaa concludes, both sides are complicit in the incitement of violence, albeit at disparate scales. Is there ever going to be an end to this regurgitation of violence? I asked. No, not when violence is the first resort. Violence will sell more guns and take more lives – that’s about it.

What about peace talks? The West, particularly the United States, is at the helm of peace talks. As with many things, it has become more of conflict management rather than conflict resolution.

My conversation with Bahaa was necessitated by the need for a better appraisal of the Israeli-Palestinian situation. But I also wanted to look at it from the standpoint of displaced, discarded bodies forced to move or become casualties of border politics in the modern notion of nation formation.

What becomes obvious is that the method and approach to the formation of the Israeli nation-state is one forged in the crucibles of 19th-century colonialism. It is necropolitics, that is, the entitlement of a nation-state to legal power – shored up by capital and powerful alliances – to inflict death with impunity. This colonial disposition is carried over to our time, thereby sabotaging hopes of the 21st century being one of healing and reparation.

No one is genuinely committed to a decolonial future who shouldn’t be invested, if not implicated, in the concerns of Isreal and Palestine. The situation, as it stands, represents the most atrocious form of colonialism at play in our supposedly post-colonial time.

Support the show (https://www.patreon.com/nkatapodcast)